Fatma Esen

On Sunday, November 2, 2025, Mary Tezak and I wandered through the Feriköy Antique Bazaar in Istanbul, looking for anything connected to our research on Hatay and Trabzon. Deep inside the market, we stopped at one of the largest stalls, crowded with old photographs and press materials. Digging through a box of mixed papers, postcards, newspapers, a wedding card written in Armenian, a few Greek items, and several Arabic booklets and manuals, I grew curious and asked the seller where the box came from. He told us it belonged to an Armenian family in Kurtuluş; after the mother passed away, her children had cleared out her belongings.

It wasn’t an unfamiliar story for Istanbul. Once known as Tatavla (Ταταύλα), today’s Kurtuluş had long been home to large Orthodox Greek communities, along with Armenian and Jewish residents who settled there by the nineteenth century. Though the neighborhood changed over time, older residents often recalled how its relative poverty fostered a sense of social cohesion and a shared subculture with its own festivals, foods, and meyhanes.

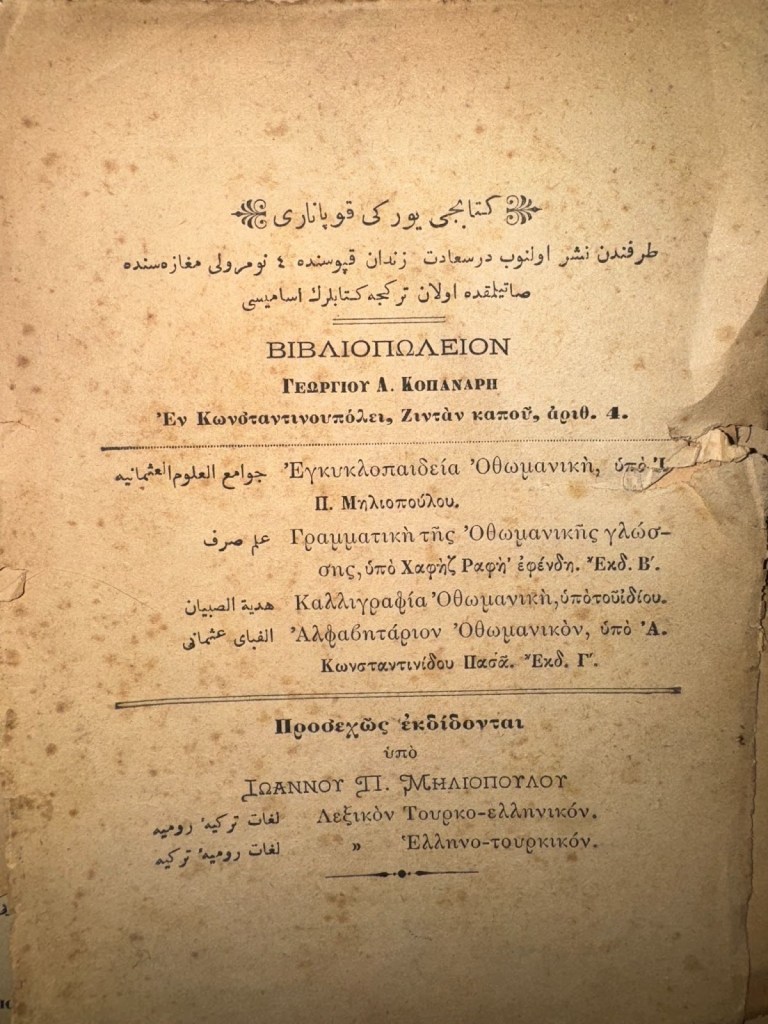

After learning the box’s origins, I focused on the Arabic-script materials, as there were only a few Armenian items. Most were Qur’ans, instructional booklets on Qur’anic reading, and several Ottoman handwritten letters likely written by the same woman. Yet one item immediately drew my attention: a text written in both Arabic and Greek characters. The book was in very poor condition, scattered into torn fragments that I tried to piece together. With the introduction missing, I could not identify the title. Assuming it was a Karamanlidika (Turkish written in Greek script) book, I bought it for 200 liras and headed home, while Mary purchased a family photograph from Hatay.

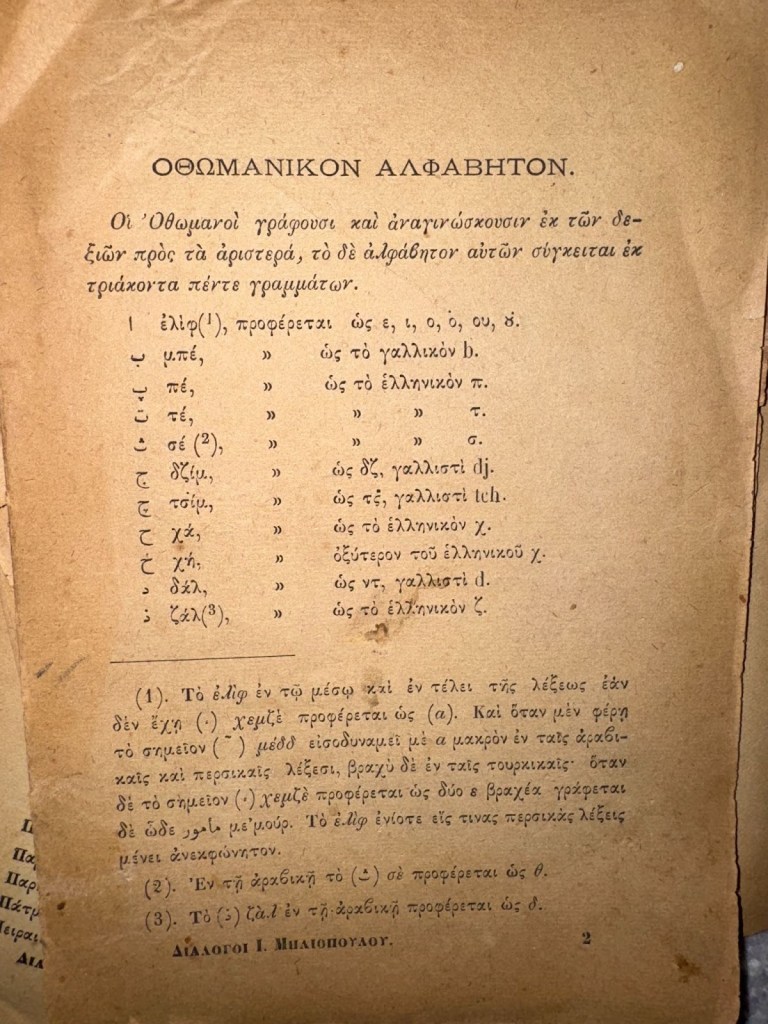

As I continued examining the book, especially the dictionary section, I realized it was not Karamanlidika at all; the Greek entries did not match the Ottoman Turkish translations. The surviving first pages introduced Arabic letters to Greek readers, explaining pronunciation, positional variations, and the equivalents of certain Greek letters in Arabic script. At the bottom of one fragment, I noticed the line ΔΙΑΛΟΓΟΙ Ι. ΜΗΛΙΟΠΟΥΛΟΙ (Dialogues of I. Miliopoulos). Then on page 25, the full title appeared: ΔΙΑΛΟΓΟΙ ΕΛΛΗΝΟΤΟΥΡΚΙΚΟΙ ΚΑΙ ΤΟΥΡΚΟΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΙ, or Mukālemāt-ı Rûmiyye-i Türkiyye ve Türkiyye-i Rûmiyye (Greek–Turkish and Turkish–Greek Dialogues). Only after reading Livanos and Balta’s excellent article did I fully understand what I was holding: a Greek–Turkish language textbook written by Yanko (Ioannis) P. Miliopoulos, an official in the Ottoman Translation Office (Rüsumat Emaneti Tercüme Odası).

Miliopoulos, whose name I first encountered through this very book, was born in Trabzon in 1852, the same region where my own research is rooted. He came from a Phanariot family and studied at the Phrontisterion of Trabzon, and from the way he wrote about the city, he seems to have been genuinely proud of being a Trabzonlu. But in 1871, he left for Istanbul. The Phanariots, named after the Phanar (today’s Fener) quarter of Constantinople, had played major roles in the Ottoman bureaucracy during the eighteenth century, serving as dragomans for the Sublime Porte and foreign embassies, and, in some cases, as hospodars in the Danubian Principalities until the Greek Revolution of 1821. Miliopoulos’s own bureaucratic life unfolded in the quieter aftermath of this world; he worked as a translator and censor in various departments and later at the customs office of Galata. Yet unlike the prominent Phanariot families who dominate the historiography, his story belongs to a different register, a humble trajectory shared by those who remained in the empire after the Revolution, held modest posts, lived ordinary lives, and navigated its multilingual landscape with little fanfare.

Early in his career, he produced language and history textbooks for Rum (Ottoman Greek) schools. He translated several works and devoted considerable attention to materials that would help students learn Ottoman Turkish. The motivation was partly political because anyone seeking entry into the Ottoman bureaucracy needed Ottoman Turkish, the official administrative language. After the 1869 education reform, which mandated Turkish-language instruction in non-Muslim schools, Rum, Armenian, Arabic, and Jewish intellectuals across the empire began producing textbooks, bilingual grammars, and dictionaries in both Turkish and their own communal dialects (Livanos & Balta 2023, 350–51). Miliopoulos understood this shift well and was likely familiar with earlier Karamanlidika efforts.

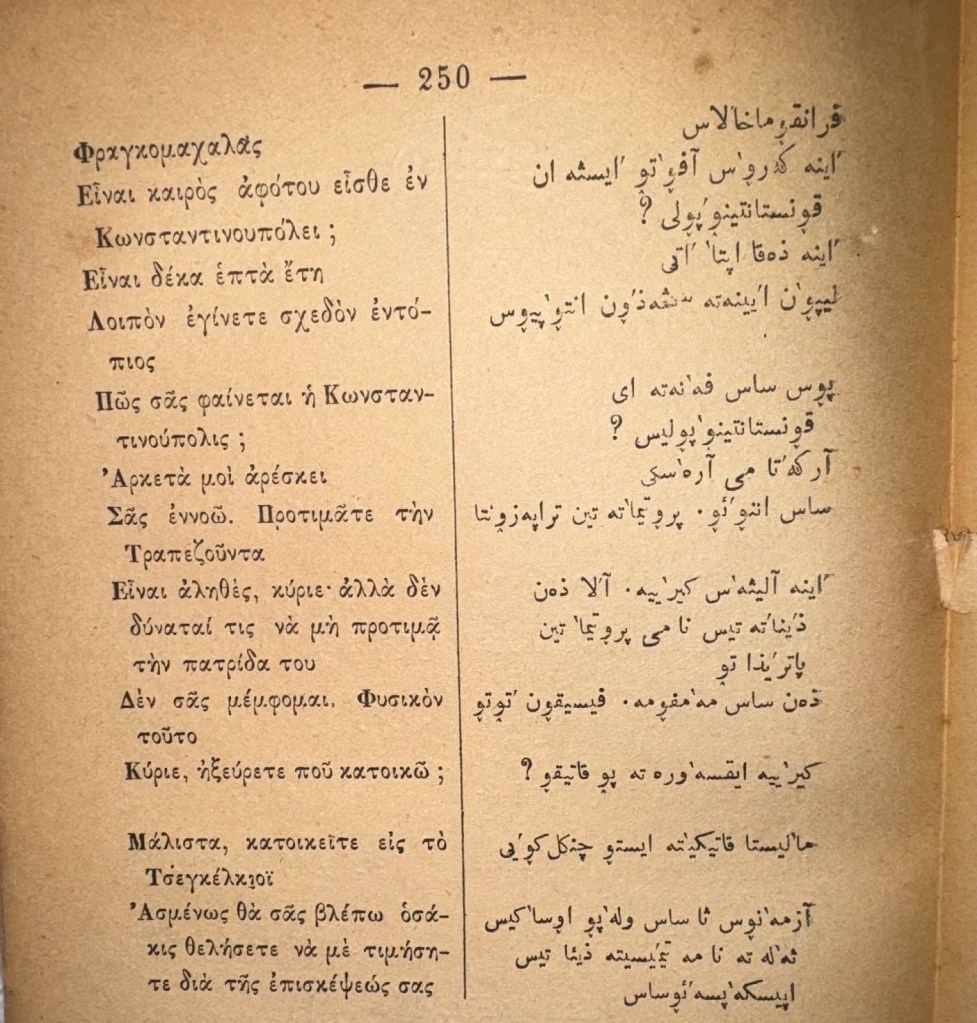

According to Livanos and Balta, the preface of Mukālemāt (missing in my copy) emphasized how teaching the Turkish language helped create a sense of uniformity in a multilingual and multinational society. Miliopoulos also stated that his edition had a dual purpose: not only to serve the needs of Rum readers but also to assist Turkish speakers who wished to learn Greek. For this reason, he transliterated Greek words into Arabic characters and juxtaposed them with their Turkish equivalents, written in both Greek and Arabic scripts (Ibid., 355). This was precisely the reason I initially mistook the book for Karamanlidika.

To cut it short, the copy I found turned out to be the second revised edition of Mukālemāt, published in Constantinople in 1887 by the Vivliopoleion of G. Kopanaris (Zindan Kapı No. 4). The revised edition honored Sultan Abdülhamid II and presented Greek and Turkish texts side by side, transliterated into both scripts, with dialogues, vocabulary lists, and terminology drawn from daily, political, and religious life.

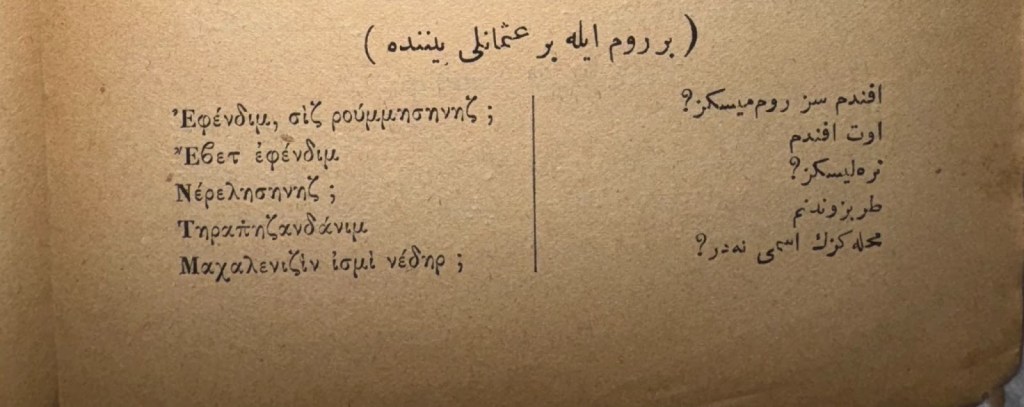

Pages 17–18 introduce the Arabic alphabet with Greek phonetic explanations (e.g., ا for ελιφ and ج for τσιμ). Page 19 displays the printed (matbū) and handwritten (rikā) forms of both languages. Page 22, under “ΠΡΟΦΟΡΑ” (Pronunciation), lists Turkish words transcribed in Greek letters. The dictionary is organized thematically, “On the State,” “Days of the Week,” “Regarding the Universe”, and includes verb conjugations in both languages. A striking example appears on pages 251–252 in a dialogue titled “Bir Rum ile Osmanlı Beyninde” (“Between a Rum and an Ottoman”), where the Rum identifies himself as from Trabzon and the Ottoman as from Constantinople, the conversation presented first in Turkish and then in Greek in parallel columns.

So what happened to Miliopoulos, the writer of Mukālemāt, whose forgotten textbook I found in Tatavla? Beyond this work, he wrote, edited, and translated several other texts while living in Istanbul. Over time, however, his interests shifted toward archaeology, particularly Byzantine monuments along the Bithynian coast near Constantinople. This passion became his primary field of research, which he pursued until his death in 1929 in Athens.

As for my own path, I began and finished writing this piece in Fener, once the neighborhood of Phanariot families like Miliopoulos’s ancestors, using this forgotten 1887 textbook to learn Greek, as Miliopulos intended in his preface, while preparing to travel to Trabzon for my own research on the Black Sea, I realized that I was, quite unintentionally, tracing the reverse direction of Miliopoulos’s life.

*The main sources for this piece are Evangelia Balta and Nikolaos Livanos, “The Ottomanist and Byzantinist Ioannis P. Miliopoulos (1852–1929),” The Historical Review/La Revue Historique 20, no. 1 (2025): 345–369; and https://www.indyturk.com/node/377646/k%C3%BClt%C3%BCr/i%CC%87stanbul-semtleri-tatavladan-kurtulu%C5%9Fa-nerede-o-karnavallar

Cover image: Abdullah frères, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fatma Esen is a fourth-year PhD candidate in the History Department, working on the environmental history of the late Ottoman Black Sea, with a focus on the commercialization of fish, fishing technologies, and the political ecology of fisheries in the long twentieth century. She is currently conducting archival and field research in Istanbul and Trabzon.