Tim Esau

Please be advised that this essay contains artistic depictions of sexual violence and atrocity.

When I first conceived of this article, I believed that while the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki may have been justified by the lives they saved in Southeast Asia. Yet after the esteemed pProfessor Toshihiro Higuchi reviewed my equivocation-heavy first draft, he recommended a monograph titled Bombing Civilians that alleviated my ignorance. Yet I still think there is value in challenging the traditional dialectic surrounding the bombings.

Nearly all scholars in popular and academic historiography neglect the voices of those in Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia. Authors engage with the attack as a punitive measure against Pearl Harbor, employ the counterfactual of losses in an American invasion of the mainland, or foreground the idea of a Soviet split of mainland Japan, but ignore the voices of the four hundred million subaltern subjects of the Japanese empire. Both casual and scholarly engagement with the bombing ultimately frames it as a wartime conversation. For instance, in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, the American government sought to rectify potential cognitive dissonance between the rightfulness of the Allies in WWII and the murder of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians. According to Professor Tomoko Takada, the official campaign encouraged stories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to be told alongside atrocities committed by the Japanese against American soldiers during the war, particularly of the Bataan Death March and Pearl Harbor. While this coupling may have been effective for reducing the cognitive dissonance of post-war Americans, conservative Japanese are left to wonder why their—albeit harsh— wartime actions against soldiers merit the annihilation of civilian cities. This American campaign simply foregrounded atrocities committed against a wartime enemy which are certainly more easily dismissed than those committed against ostensibly protected imperial subjects. Japanese philosopher Hitoshi Nagai stresses what he sees as the result of this discourse: “Japanese people’s [everpresent] awareness of themselves as victims [has] also prevented them from internalizing other people’s war experiences.” At the turn of the 20th century, the Japanese, armed with pan-Asianist rhetoric, began to establish an empire across East and Southeast Asia, which would span a territory and population over twice that of the Nazis at their peak. Yet under their rule, many endured senseless violence due to the dehumanizing ideology of the metropole. For instance, it is possible that 1,430,000 Indonesian forced laborers conscripted by the Japanese died thanks to indifference towards health. Therefore, I will foreground narratives from Southeast Asians that coincide with the bombing.

In Fifty Years of Silence, Indonesian-born Jan Ruff-O’Herne highlights her experience of being forced into sexual slavery and subsequent shipment to a concentration camp where other ex-“comfort women” were left to die. She describes how, at this camp, death “was still all around, with women and children dying every day.” Her sister had “virtually stopped growing” because of the lack of food. Only when she saw “not Japanese planes… but allied planes” flying “over our prison camp” did O’Herne express “what excitement there was.” According to her, the war in Java ended on 15th August, after the 6th August bombing of Hiroshima.

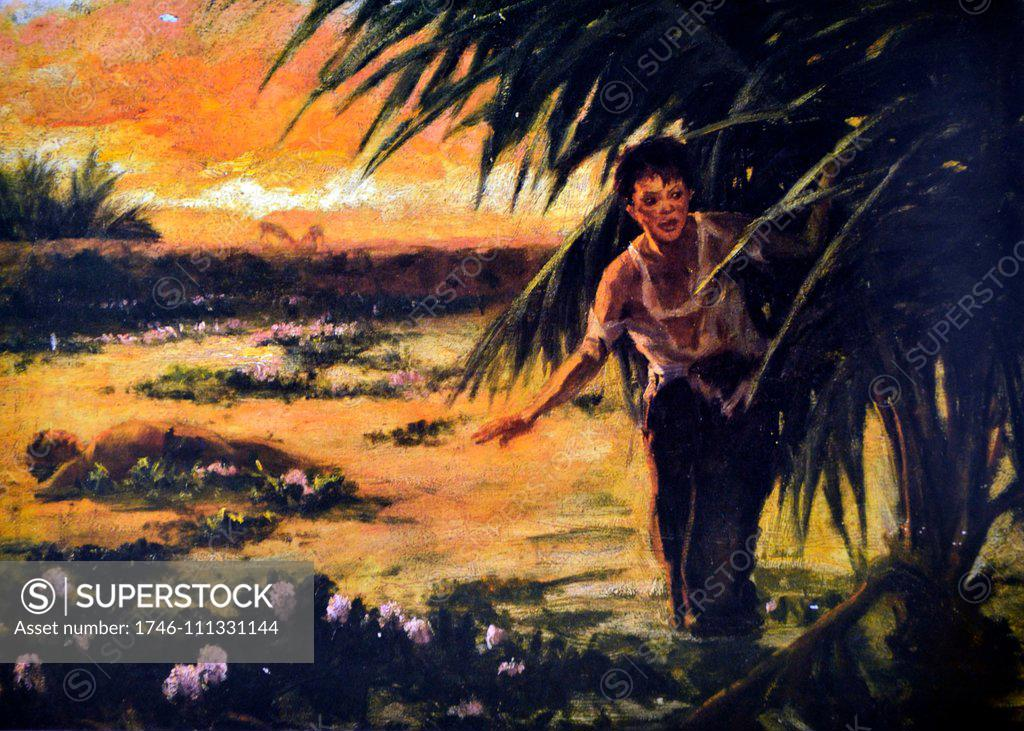

In 2024, I had the pleasure of visiting the excellent National Museum of Fine Arts in Manila. I imagine Gallery-VIII (known colloquially as the “War Gallery”) sticks with other visitors as it stuck with me. Here are a few paintings from the gallery.

Fugitive This painting depicts a man attempting to escape Japanese soldiers.

A Tragic Lesson, depicts the fall of Bataan

Ravaged Manila depicts Manila during the liberation from Japanese bombardment

The anguish captured by these Filipino artists reveals an understanding of Japan and its withdrawal wholly unknown to Japanese victim awareness. Nagai witnessed this understanding during a conference in Kawasaki-City, when Filipino novelist F. Sionil Jose pushed back against an Indian author who expressed sympathy for Hiroshima. He emphasized that the “A-bomb attacks were the natural consequence of Japanese actions” and that Filipinos at the time “wished that… Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and all other areas would have been attacked.” Summarizing Filipino sentiment in one of his interviews, Nagai reiterates: “Juan Jose P. Rocha, twelve of whose relatives were killed by Japanese soldiers in the Battle of Manila, felt frustrated by Hiroshima’s privileged status as a world-famous city, which was far above that of Manila.”

In my own experience, the remnants of Japanese occupation are palpable. During my four years at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, I heard many urban legends of Japanese occupation. Just under a mile away from the university is Mang Gui Kiu (猛鬼橋) or Ghost Bridge. Considered one of the most haunted spots in Hong Kong, it certainly has a bloody history. Apart from a 1955 flood that killed 28 children, the area is also rumored to have been a Japanese execution ground during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). This entire region of Tai Po is considered haunted, with many villagers claiming to hear marching sounds at night. The horrors of Japanese occupation reached such an extreme that even the local Chinese population, which was not generally forced into concentration camps, has orally passed on these stories.

Former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (LKY) remembers similar horrors. He recalls that those “who saw the Japanese soldiers in the flesh cannot forget their almost inhuman attitude to death in battle” and posits that “had the British re-invaded and fought their way down Malaya into Singapore, there would have been immense devastation.” Therefore, he claims: “I have no doubts whether the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary. Without them, hundreds of thousands of civilians in Malaya and Singapore, and millions in Japan itself, would have perished.” According to him, the bomb spared Singapore (and other South East Asians) the “fiery ordeal that had been the fate of Rangoon and Mandalay.” The Burma campaign led to the deaths of 250,000 to 1,000,000 civilians.

I would be remiss to take LKY’s remarks as objective fact. As Yuki Tanaka highlights, not only did the Japanese government fail to concede to the Allies immediately after the bombing, but the Supreme War Council—the centralized advisory body for war guidance in Japan—did not even convene until days later. Instead, hours after Soviet tanks crossed into Manchuria, the council decided to meet and discuss terms of surrender, which would leave Japan intact while preserving Hirohito and the imperial system (115). Even still, a textual analysis of LKY’s rhetoric reveals the extent of Japanese abuse; even though he worked for the Japanese propaganda department (Hodobu) during the war, Japanese wartime acts evidently colored his perception to the extent that he felt compelled to justify the massacre of civilians.

I am not claiming the bombing to be anything but horrible or that the bomb should have been used punitively. Nor that the American who dropped the bombs considered the wellbeing of Southeast Asian civilians. In fact, as Tsuyoshi Hasegawa points out, for many American wartime officials, latent racism undergirded decisions that justified the indiscriminate killing of Japanese civilians (119). Instead, my choice to highlight Southeast Asian voices is twofold. Firstly, this discourse challenges the victim awareness Nagai revealed. This awareness prevents many right-wing Japanese from internalizing other people’s war experiences. I believe that their rightful status as victims needs to be bundled up with the recognition of their atrocities. I liken this to the oft-repeated mantra “History did not begin on October 7th.” Japanese soldiers continued to butcher and enslave their imperial subjects up until the last minutes of the surrender— in some cases, much later (see No Surrender by Hiroo Onoda). Secondly, I hope authors can pay more attention to the voices of the subaltern in the Japanese empire, rather than entertaining tired American-centric debates.

A survivor in the Theresienstadt Ghetto famously stated: “We cried for joy when we saw the red glow in the sky. Dresden is burning, the Allies are not far away!” I wish that scholars would try to recover the cries of those south of Japan.

Cover image: Legislative building in Manila, Philippines (via Harry S. Truman Library & Museum)

Timothy Esau is a first-year MAGIC student who is interested in the South Asian diaspora and its relation to ethnogenesis, particularly in the East Asian context. He previously obtained a Bachelor’s of Business Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.